Art As a Rhetorical Tool: Visual Rhetorical Analysis of Anti-War Artworks From the 20th Century

Art has been a medium of expression and communication since humans gained consciousness and were able to interact with one another. As humans evolved, so did art and the way they—and specifically artists—used it to express their ideas, emotions, and beliefs. However, one thing remained almost constant throughout this change: the want to convey meaning. Many postulations have been made as to the purpose of art and why artists create art, ranging from the pleasure derived from its aesthetic appeal to its importance in social development (Sherman and Morrissey 1). Nevertheless, this paper will focus on two critical purposes of art: visual appeal and its use as a rhetorical tool. In their pursuit of conveying meaning, artists created art both in times of joy and suffering. One of these times of suffering when artists created art the most was during times of war. During times of war, artists questioned and critiqued war—they created works that appealed to the masses and to those in power to put forth the notion that war is bad and shouldn’t be pursued. The 20th century saw many wars, which in turn led artists to do what they did best: create works that expressed their ideas for or against a cause. Although many artists created anti-war artworks in the 20th century, the most effective and powerful examples in terms of rhetorically conveying their message and visual exquisiteness are by the artists Picasso, Kollwitz, Reuterswärd, Nevinson, and Kubrick.

Visual works of art can be interpreted and analyzed in many different ways, however, visual rhetorical analysis helps us better understand what makes some works of art better convey their meaning. Before elaborating on the term ‘visual rhetoric,’ the term ‘rhetoric’ itself must be briefly mentioned. The term originated in Ancient Greece as the art of writing and speaking effectively, with the goal of persuading others (Mazzei). In essence, rhetoric is a tool that helps convince or at least appeal to others with an agenda. Rhetoric focuses more on the way a thing is said than what is actually said. As a result, it is heavily used in literature, law, politics, and even daily conversation. Due to its nature, rhetoric has been heavily associated with speech and writing—both being mostly non-visual means of expression and communication. In time, however, as both art and rhetoric progressed, the term ‘visual rhetoric’ became more important in understanding art. Visual rhetorical analysis differs from analyzing an artwork aesthetically or via its place in art history as it specifically aims to understand how art creates meaning (Edwards 220). Ergo, visual rhetoric is how artists convey their messages through their works rather than what they try to convey—relating back to how ‘rhetoric’ works.

Another concept in interpreting the meaning of visual artworks is “Layers of Signification” put forth by Kopper, focusing on how art can transcend the artist’s intentions as to the meaning of the artwork. The first layer of the significance of an artwork is created via the semiotic attributes of the artwork relating to the artist who created the visual (Kopper 448). Kopper argues that the context in which the artwork was created either intentionally or unintentionally is referenced by the artwork—this reference, for example, may relate to the styles of other artists that were of influence (448). The second layer of significance comes from the way the artwork is presented to the audience: where the artwork is displayed, whether it was created after a particular event, the form of the artwork (mural, painting, etc.), etc (449). This layer, similar to the first one, adds to the initial composition of the visual and how the artists aimed for it to be perceived. However, moving forward, the third and fourth layers of significance relate to the impact the artwork has had, i.e., the preceding meaning it obtains, after its creation, such as artworks inspired by the initial artwork or how the image of an artwork is used to further other peoples’ messages in addition to the initial meaning that was intended by the artist (449). Although the ‘layers of signification’ may not apply to any and all works of art that were created with the intention of conveying the artist’s intended meaning, it helps us better understand how works of art can be used in more intricate ways to inculcate secondary or even tertiary meanings.

The first painting that will be analyzed in terms of visual rhetoric, Picasso’s Guernica, can be considered the epitome of anti-war art due to how Picasso used visual semiotic symbolism and the ‘legend’ of Guernica, per se, went beyond time and Spain.

Art historians visually analyze Guernica by dividing it into geometric shapes (rectangular and triangular) and panels: a rectangular panel to the right with three women and a horse, another rectangular panel to the left with another woman and a bull, and a final, triangular panel in between that helps emphasize the human suffering that is depicted on the artwork (Cantelupe 18). Many more readings focusing on specific semiotic elements are brought about to the painting that relate to classical Greek dramas and the fight between two contemporary ideologies—communism and fascism—even though Picasso himself says that was not his primary intention with the painting (19-20). However, it can be argued that the simplest yet most powerful reading that can be brought about to Guernica is the fight between good and evil—light and dark. The painting itself is made up of shades of gray, black, and white. Scenes of suffering and tragedy are interlinked with an overarching source of light—a sun that is illuminated by a lightbulb—and a woman holding a gas lamp. Guernica is successful in using visual appeal as it joins semiotic elements from contemporary symbols of the Spanish Civil War (bull, horse, the tragedy of the women, etc.) whilst captivating the interest of the audience with its unorthodox composition. Picasso’s cubist style takes a different approach to capture the tragedy of the Spanish Civil War by not depicting war as is but through implicit visual symbols and creating his own meaning through the creation of a chaotic, brutal yet universal scene of suffering—championing the anti-war art genre. Guernica’s meaning, however, does not end there. Relating back to the layers of significance, we can observe how Guernica was able to gain its own additional layers of meaning as time progressed through two critical examples.

In 1947, Iranian Tony Shafrazi smuggled a can of red spray paint into the Museum of Modern Art in New York City and wrote: “KILL LIES ALL” onto the famous painting to raise awareness regarding the massacre at Mỹ Lai during the Vietnam War (Kopper 449). With this act of vandalism, Shafrazi added his own layer of significance to the painting. It can be easily argued that Picasso had probably not intended his work to be used to protest against a specific massacre that happened decades later, i.e., that was not his meaning. However, Guernica was so powerful of a visual that Shafrazi chose it as his medium of protest—he did not use any ordinary wall or surface to protest, he chose Guernica. As a result, in addition to the visual rhetoric Picasso used with his semiotic symbols in creating Guernica, the painting itself, as a whole, served as a rhetorical device in furthering the anti-war narrative. Lastly, the painting was used directly as a medium of visual protest, without change, even in protesting contemporary wars. In the early 2000s, many protestors around the world took to the streets to protest the war in Iraq with prints of Guernica as signs (450). They chose to use the image of the painting rather than writing messages such as ‘No War’ as, through time, Guernica meant to mean exactly that. Picasso had initially created Guernica to protest against the atrocities that had happened in the town of Guernica, Spain during the Spanish Civil War but through time, his work came to truly mean ‘No War’. Through the visual analysis of the painting in Picasso’s semiotic symbolism and how, through time, the painting itself became its own rhetorical device, we can observe that Guernica is a true anti-war painting. It is so powerful that it went beyond the description of being ‘an anti-war x or y’ but came to truly mean the phrase ‘anti-war’.

Kollwitz’s work, on the other hand, takes a different approach to creating anti-war art and creates powerful meaning as she utilizes mass-produced and comparatively simple imagery. Käthe Kollwitz was an artist that was prominent in the “No More War” movement of Germany between 1920 and 1925 who chose to use printmaking as her main tool of delivery (Murray 1). Kollwitz aimed to reach as many people as she could rather than limiting the display of her work to a gallery or museum (2).

![Fig. 3. Käthe Kollwitz, Nie Wieder Krieg! [No More War!], 1924 Fig. 3. Käthe Kollwitz, Nie Wieder Krieg! [No More War!], 1924](https://www.kollwitz.de/img/inhalt/Sammlung/Plakate/kollwitz-nie-wieder-krieg_kn_205-iii-b_2000px.jpg?w=0)

Nie Wieder Krieg! or as it is translated into English, No More War! was the most prominent symbol of the anti-war movement in Kollwitz’s time (14). One of its first appearances was on the cover of the anti-war edition of the newspaper Leipziger Volkszeitung in which Kollwitz used two very important visual rhetorical tools in making her simple illustration powerful: the androgynous composition of the illustration and the use of the Schwurhand [Oath Hand] (14-15). As Kollwitz used a figure that didn’t emphasize a specific gender, her artwork was able to serve as a universal symbol of the anti-war movement (14). Additionally, by incorporating a common symbol used in Germany when taking oath at the time, the Schwurhand [Oath Hand], she was able to pass on the meaning that the illustration is taking a solemn promise for the anti-war effort (15). It can be argued that Kollwitz chose more of a pragmatic rather than an artistic approach in creating Nie Wieder Krieg!. The rushed and simple nature of the illustration, in addition to how it was mass-produced, helps illustrate how Kollwitz’s primary goal was to further the anti-war movement where her art served as a mere rhetorical tool. By incorporating common semiotic symbols of her time, Kollwitz was able to build strong grounds for the first and second layers of significance in her artwork. It can also be argued that those who reprinted her work, used her illustrations as their own rhetorical devices, adding to its layers of significance by featuring them in their own mediums.

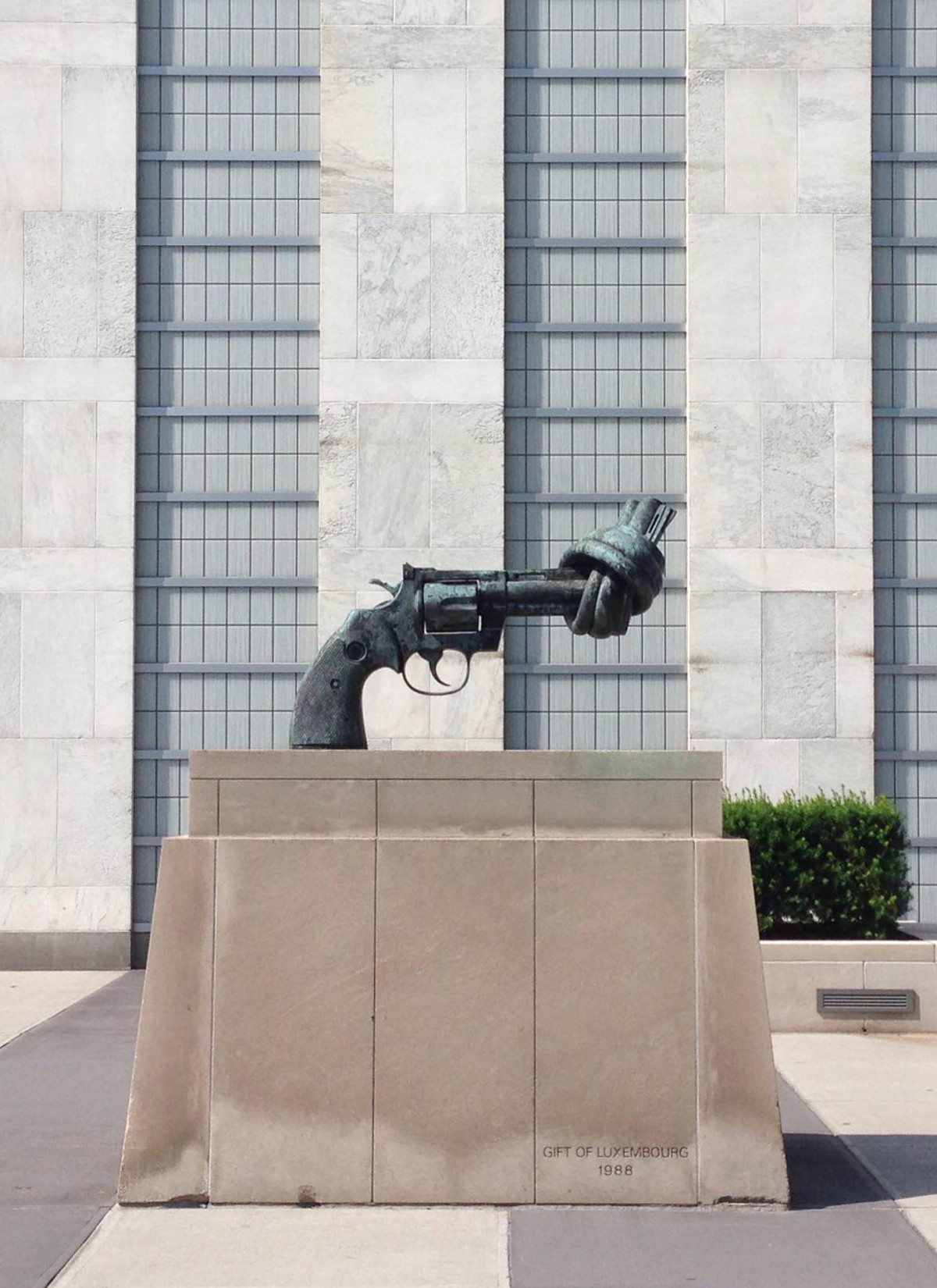

Differing from the establishment, Reuterswärd, in his sculpture Non-Violence, also referred to as ‘the knotted gun,’ uses a counterintuitive rhetorical method to put forth an anti-war meaning.

Reuterswärd created the first iteration of his famous sculpture back in 1980 after his friend John Lennon—who was also known for his vision of peace around the world—was assassinated (Cespedes 113). Later on, many more replicas of the gun were made and even one is located outside the United Nations Headquarters in New York (114). The sculpture features a revolver with its barrel tied in a knot—hence its nickname, ‘the knotted gun’. The gun is cocked, meaning it is ready to shoot, but the knot on the barrel implies that it can’t. The knotted gun is a clear and simple example of anti-war and anti-violence art. However, the way it achieves this meaning—through the use of a device of violence—is rather intriguing. Traditionally, when we think about symbols of peace, the first thing that would come to mind wouldn’t be related to a tool of violence—maybe a dove, or an olive branch but rarely a gun. Nonetheless, Reuterswärd takes an avante-garde approach to his meaning. Regardless of the counterintuitive nature of Non-Violence, we can observe that it has been successful in disseminating its message and serving as a rhetorical tool itself as many NGOs, NPOs, and even the UN have used its image or reproductions in their messaging (114). Thus, it can be argued that when it comes to creating anti-war artworks, the explicit use of symbols relating to violence and war may actually prove useful if done cleverly and appealingly.

Nevinson’s Paths of Glory is also a powerful, trailblazing artwork as the artist doesn’t shy away from breaking from the established narrative that war is always glorious and righteous, by depicting scenes of war as is.

Nevinson is unique among the artists mentioned in the scope of this paper as he saw firsthand the atrocities of war in the trenches of the 1st World War where he served as an ambulance driver (Doherty 64). Nevinson was commissioned by the British government to create Paths of Glory as a part of a “war-artists program” (64). However, after its creation, the painting was censored by the government as his paintings were considered “hindrances to the war effort” (67). Paths of Glory depicts two dead British soldiers lying on the hillside in the trenches of war with their rifles on their sides where this unfiltered, ‘as is,’ portrayal of dead British soldiers was considered bad for morale (63, 67). Although the focus of this paper is on anti-war artworks, because Nevinson is mentioned, the fact that not all art related to war is necessarily ‘anti-war’ should be acknowledged. Nevinson himself was initially praised for his previous works such as La Patrie which depicted wounded soldiers in a cubist style where this embrace stemmed from his unwavering commitment to depicting facts on the ground (64). Regardless, in depicting dead soldiers, it can be argued that Nevinson does not have an explicitly anti-war agenda. By depicting the war trenches as is, he lets the viewer decide how war should be perceived. Both the context in which the painting was made (a time of low morale) and how Nevinson was disillusioned by the war effort contribute to the first and second layers of significance for the artwork. Even though, as stated, he might not have an agenda one way or another, the artwork semiotically reflects such outside influences. In the end, due to Nevinson’s commitment to depicting war with unwavering realism and how the work was received afterward by the government, it can easily be argued that Paths of Glory turned out to be a staple of the anti-war art genre.

Lastly, Kubrick’s 1957 movie Paths of Glory is an important cornerstone of visual anti-war art both because of its unique approach to anti-war filmmaking and also its exploration of complex ethical frameworks. The movie takes place near the end of the 1st World War in a French-German conflict where the protagonist, Colonel Dax, is ordered to lead an assault onto the Ant Hill, a strategic target held by the enemy Germans, by his superiors—an assault which is known to most likely result in failure but is still pursued. The film explores the unfoldings of the unsuccessful assault and subsequent trial of three men from Colonel Dax’s regiment for insubordination—an acquisition and trial which is purely intended to maintain the status quo and the image of the French army and nation. The movie is unique in the sense that traditional military conflict scenes aren’t center-stage and don’t even make up most of the screen time. The movie focuses more on what happened after the fact—the acquisitions, trial, and subsequent execution of innocent soldiers. Before focusing on the plot and philosophy of the movie in depth, one of the most important scenes and the use of visual techniques in the said scene should be analyzed and reviewed.

Although not the climax of the movie, the Charge on Anthill is one of the most visually complex scenes of the movie. Kubrick uses masterful camera techniques without trying to drown out the narrative of the plot with avant-garde techniques (Eggert). In the scene, Kubrick intentionally extends the actual size of the trenches to allow Kirk Douglas (playing Colonel Dax) to be on the center stage (Eggert). After a while, he sees that he is almost all by himself as his men have fallen one by one in the failed assault (Eggert). This scene and how Dax tries to persevere despite apparent signals that the Attack has failed and will fail can be interpreted as foreshadowing to the later scenes involving the trial. Before the war, Colonel Dax was a lawyer and after hearing that three of his men will be tried for insubordination—which he knows not to be true—he offers to defend them. Similar to the failed attack on the Anthill, he knows and sees that his efforts will be futile, yet does not give up until the very last minute. The use of a grand French chateau the commander use as their center of command is also one of many visual rhetorical tools that Kubrick utilizes to better illustrate the hypocritical and vile nature of men when it comes to maintaining power no matter what. Kubrick, in the movie, tries to convey the eternal nature of a utilitarian framework that always prevails (Riccomini 324). This framework can be interpreted as the French army, nation, or even society as a whole. Kubrick tries to pass on to the viewer that societal systems will do no matter what to guarantee their existence, whether it be sentencing innocent men to death or even waging unjustified war. The movie also focuses mainly on how Colonel Dax serves as a “moral alternative” in an “immoral world” (325). Even with a gloomy and dreadful atmosphere, Kubrick does not shy away from hinting that a drop of good exists in an ocean of evil. Finally, when Colonel Dax tries to use blackmail to save his men’s lives, Kubrick makes the viewer question whether immoral means can be justified if the individual is pursuing moral ends (327). Paths of Glory is a great example of anti-war art and anti-war filmmaking as it does not fit the traditional criteria of what it means to make an anti-war movie. Flashy battle scenes only serve to set the scene for the exploration of arguably toned down and even at times silent exploration of human morality. Kubrick utilized both interesting visual and narrative storytelling techniques that make Paths of Glory a movie that not only is meaningful in its time but also in contemporary society.

In conclusion, art has been and will continue to be one of the most critical aspects of what makes humans, human. Although it is both pleasurable and educational to explore what makes great art great, when it comes to anti-war art, the fact that the catalyst for its creation is a human tragedy should not be overlooked. With varying degrees of social and political impact, Picasso, Kollwitz, Reuterswärd, Nevinson, and Kubrick were masters in using the ancient ‘art’ of rhetoric visually and in an aesthetically pleasing way. In the end, as time goes on, what we can do is hope that these artists serve as trailblazers in a future where new generations of artists can create art without having to use it as a tool to decry one of the greatest plagues of man: war.

Works Cited

Cantelupe, Eugene B. “Picasso’s Guernica.” Art Journal, vol. 31, no. 1, 1971, pp. 18–21., https://doi.org/10.2307/775628. Accessed 17 Dec. 2022.

Cespedes, Marcelo. “Marcelo Cespedes. Article. Art With A Purpose.” Art With A Purpose, 04 (2016): n. pag. Print.

Doherty, Charles E. “Nevinson’s Elegy: Paths of Glory.” Art Journal, vol. 51, no. 1, 1992, pp. 64–71., https://doi.org/10.2307/777256. Accessed 11 Oct. 2022.

Edwards, Janis L. “Visual Rhetoric.” 21st Century Communication: A Reference Handbook, edited by William F. Eadie, Sage, Los Angeles, 2009, pp. 220–227.

Eggert, Brian. “Paths of Glory.” Deep Focus Review, Deep Focus Review, 11 Aug. 2008, https://deepfocusreview.com/definitives/paths-of-glory/. Accessed 2 Oct. 2022

Kollwitz, Käthe. “Nie Wieder Krieg! [No More War!].” Käthe Kollwitz Muesum Köln, 1924, https://www.kollwitz.de/plakat-nie-wieder-krieg. Accessed 17 Dec. 2022.

Kopper, Akos. “Why Guernica Became a Globally Used Icon of Political Protest? Analysis of Its Visual Rhetoric and Capacity to Link Distinct Events of Protests into a Grand Narrative.” International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society, vol. 27, no. 4, 2014, pp. 443–457., https://doi.org/10.1007/s10767-014-9176-9. Accessed 2 Oct. 2022.

Kubrick, Stanley, director. Paths of Glory. Bryna Productions and Harris-Kubrick Pictures Corporation, 1957.

Mazzei, Michael. “Rhetoric.” Salem Press Encyclopedia, Sept. 2021.

Murray, Ann. “Käthe Kollwitz: Memorialization as Anti-Militarist Weapon.” Arts, vol. 9, no. 1, 2020, p. 36., https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9010036. Accessed 11 Nov. 2022.

Nevinson, Christopher R. W. “Paths Of Glory.” Imperial War Museums, 1917, Imperial War Museums, London, UK, https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/20211. Accessed 17 Dec. 2022.

“Pablo Picasso ‘Guernica’ / spray paint”. Art Damaged, 19 April 2012, https://www.artdamagedbook.com/blog/pablo-picasso-guernica-spray-paint. Accessed 17 Dec. 2022.

Picasso, Pablo. “Guernica.” Rethinking Guernica, 1937, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía (MNCARS), Madrid, Spain, https://guernica.museoreinasofia.es/gigapixel/en/?map1=VIS#2/76.1/-105.1. Accessed 17 Dec. 2022.

Reuterswärd , Carl Frederik. “Non-Violence.” United Nations Gifts, 1980, New York, https://www.un.org/ungifts/non-violence-0. Accessed 17 Dec. 2022.

Riccomini, Donald. “Paths of Glory and the Tyranny of the Greater Good.” Film-Philosophy, vol. 20, no. 2-3, July 2016, pp. 324–338., https://doi.org/10.3366/film.2016.0018. Accessed 2 Oct. 2022.

Sherman, Aleksandra, and Clair Morrissey. “What Is Art Good for? the Socio-Epistemic Value of Art.” Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, vol. 11, 28 Aug. 2017, pp. 1–17., https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2017.00411. Accessed 17 Dec. 2022.